By Tallulah Eyres, doctoral researcher in sociology.

Tallulah Eyres is currently pursuing a PhD in Sociology at the University of Cambridge, funded by the Economic and Social Research Council's Doctoral Training Partnership.

Her research titled "Empowering Agency: Rethinking Devolution, Local Governance, and the Local Social Contract" seeks to address a crucial question: can devolution counteract the decline in trust within our political system? It explores whether decentralising decision-making bridges the gap between national policies and local realities or whether it increases bureaucratic complexities within our democracy. By integrating concepts such as double devolution, subsidiarity, representative and participatory democracy, Tallulah's research aims to shape governance, policy-making, place-making, and enhance citizen agency and empowerment.

This blog examines the growing disconnection between British citizens and their democratic institutions, evident in declining voter turnout, widespread social unrest, and a defection from mainstream to populist candidates and parties. It argues that these are not isolated phenomena but are deeply rooted in historical and socio-spatial contexts that shape political attitudes and behaviours. It explores the plight of 'left behind' areas and evaluates the potential of 'pride in place' as a strategy for democratic renewal.

Political participation is the essence of democracy, with voting its most visible and quantifiable expression (Whiteley, 2012). Voter turnout is therefore a ‘crucial barometer of democratic vitality’ (Barber, 1984), reflecting citizens' engagement with the political process (Powell, 1982). Voting transcends mere ritual; it embodies democratic practice, allowing citizens to exercise power, hold leaders accountable, and influence governance. Without active participation, democracy risks becoming a hollow facade rather than a responsive and representative system.

The 2024 UK general election has exposed a growing disconnection between British citizens and their democratic institutions, evident in dismal voter turnout, widespread social unrest, and a defection from mainstream to populist candidates and parties. The sharp decline in turnout signals political dormancy and resignation (Stoker, 2006) (Will Jennings, 2017), while the rise of populist parties like Reform UK and recent race-related riots reflect deeper public frustration and disillusionment (Hernández, 2018). These are not isolated phenomena but are deeply rooted in historical and socio-spatial contexts that shape political attitudes and behaviours. Local economic conditions, particularly increasing inequality and poverty, play a crucial role in this dynamic, contributing to growing disenchantment with the political system and making 'left-behind' communities more vulnerable to the divide-and-conquer strategies of populist parties. Although some attribute this behaviour to conservative social mores (Inglehart, 2019), there is limited consensus on its origins and how they are affected by factors exogenous and endogenous to local communities.

In seeking to understand the underlying causes of this disconnection, this blog will explore the plight of 'left behind' areas and the potential of 'pride in place' as a strategy for democratic renewal. By shifting the focus from national to local issues, it argues that place-based devolution and enhanced local accountability could offer solutions to the current democratic crisis. Places are dynamic and interconnected, shaped by both internal and external factors, and must be understood within their broader context. Their complex and sometimes conflicting identities, influenced by historical and social processes, reveal geographical fragmentation and can provoke defensive, reactionary responses such as nationalism, sentimentalised heritage recovery, and antagonism towards newcomers (Massey, 1994). However, these places also foster a sense of relatedness, rootedness, and belonging through their place-based identity. Redistributing power to include those marginalised from political and economic processes could harness these identities to re-engage citizens in meaningful ways and revitalise democracy.

Labour’s supermajority in Parliament, while superficially impressive, masks a deeper fragility (Baker, 2024). With only 33.7% of the popular vote, Labour’s dominance reflects more the failures of the Conservative Party than broad enthusiasm for Labour itself. This disparity highlights Labour’s precarious majority and the political drift and disillusionment affecting millions of citizens. The decline in citizen engagement diminishes pressure on officials to maintain accountability, allowing power to concentrate among elites, media, and influential interest groups. This trend towards de-democratisation is worsened by the rise of a ‘consultocracy,’ where consultants, rather than merely advising, become active government partners. This dynamic risks undermining the moral and ethical goals of policymaking by neglecting the needs and aspirations of ordinary citizens.

While the general election results highlight significant challenges for British democracy, focusing exclusively on national issues and election outcomes has limitations. In an era characterised by "post-politics" (Swyngedouw, 2015), where traditional political ideologies are increasingly blurred, understanding local political struggles and more subtle forms of political power is crucial. The 2024 local and mayoral elections exemplify this, with Labour securing control of nine out of ten metro mayoral positions across England. This victory not only reflects Labour’s expanding influence but also highlights the importance of socio-spatial relations and local ‘political biographies (Halvorsen, 2020). It demonstrates Labour’s strategic approach in building a diverse coalition and employing a multi-scalar governance model that integrates local, regional, and national policies (Diamond, 2023).

Given these developments, should the Labour Party consider devolution as a solution to the democratic crisis? Decentralising decision-making and shifting power to local communities could help Labour rebuild trust and make governance more responsive to citizens' needs. Metro-mayors, with their local mandates, play a crucial role in this by staying closely connected to their communities and advocating for local action beyond their formal powers. By ensuring that power is proportionate to its impact, Labour can amplify the voices of ordinary people and support genuine grassroots democracy, ultimately creating a more inclusive and responsive governance framework.

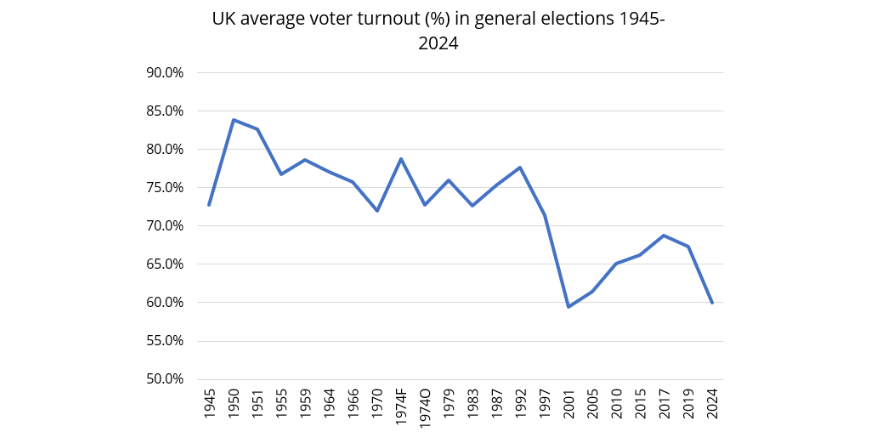

Figure 1. Sources: Statista; BBC; UK Parliament, House of Commons Library.

The decline in voter turnout, as illustrated by the 2024 election (figure 1), signals a profound crisis in political representation and legitimacy. Voter turnout has steadily fallen from 67% in 2019 to around 60% in 2024, approaching the historic low of 59% recorded in 2001. This decline sharply contrasts with the 83.9% turnout of the 1950 election, with seven of the eight highest turnouts occurring between 1950 and 1992. This electoral backslide signals a deeper erosion of trust, with many citizens perceiving their votes as inconsequential and the act of voting as a hollow ritual (Whiteley, 2012)

Moreover, official voter turnout figures based on registered voters may not fully capture the extent of political disengagement. Statistics often overlook eligible voters who remain unregistered. According to the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR), when turnout is measured as a percentage of the entire adult population, the 2024 figures drop even further to a mere 52% (Valgarðsson, 2024). The IPPR suggests that if non-voters were considered a political party, they would command the largest share of support. Additionally, the cross-party Levelling Up, Housing and Communities Committee has identified significant flaws in the electoral registration system, with up to 8 million people potentially disenfranchised due to registration issues (Levelling Up, 2024). This problem disproportionately affects those in precarious housing, ethnic minorities, and individuals from lower socio-economic backgrounds. These findings raise urgent questions about the future of British democracy and the paradox of representation: how can democracy fulfil its promise of collective self-rule and uphold human agency when so many are excluded from or reject the process?

To understand today’s voter disengagement, it is crucial to consider the historical context. The 1950s, often idealised as a 'golden era' of British democracy, were marked by exceptional civic engagement (Jenkin, 1950). The post-war period, unified by a struggle against fascism, saw significant economic growth and welfare state expansion, fostering strong civic solidarity and collective responsibility. The Labour Party, under Clement Attlee, campaigned on enhancing living standards and expanding the welfare state, while the Conservative Party (1950) advocated for enterprise and reduced public spending. These clear ideological divides resulted in 89.6% of voters supporting one of the two major parties, marking a period of strong partisan alignment and political stability (Wheeler, 2015). This era exemplified British parliamentary majoritarianism, or ‘representative democracy,’ a system that its proponents argue provided strong executive leadership and decisive governance for the national good.

Today's political landscape, shaped by the global COVID-19 pandemic and the ongoing cost-of-living crisis, starkly contrasts with the more stable and cohesive political environment of the 1950s. These contemporary challenges have fragmented society and diminished public engagement. Unlike the mid-20th century, when voter loyalty was deeply influenced by class and community ties, today's electorate is increasingly fluid and less anchored by traditional allegiances (Clements, 2015). Voters increasingly have shifted their support based on evolving personal concerns, reflecting greater political volatility and a consumerist approach to politics. Globalisation has further exacerbated this sense of dislocation. The increased mobility of people, ideas, and capital has intensified feelings of alienation among those who feel detached from their local communities. This has created a divide between the "somewheres," who feel a strong connection to their localities, and the "anywheres," who identify more with a global or cosmopolitan perspective (Goodhart, 2017). This dynamic highlights the impact of globalisation on personal and political identities.

Labour's current strategy, which focuses on attracting private sector investment to drive economic growth rather than expanding the welfare state or bolstering public services, has blurred the distinctions between the major parties. Labour’s choices may be constrained by fears of moving outside of the market consensus on macroeconomic constraints following Liz Truss’s mini budget. However, this ideological convergence has contributed to voter distrust and disengagement, as many citizens increasingly question the significance of their vote when party policies appear indistinguishable and fail to address their needs effectively. This trend was particularly evident in the 2024 election, where Labour achieved its lowest-ever vote share in deprived areas while securing its highest in affluent ones (Malik, 2024). This shift constitutes a “new frontline” in British politics, where the “left behind” have been replaced by the “well ahead” in terms of political significance, and where the Labour Party's traditional connection with the working class has weakened significantly (Robinson, 2024 ).

In his first speech as Prime Minister, Keir Starmer called for a ‘rediscovery of who we are as a nation, prioritising the country over party interests’ (Prime Minister's Office, 2024 ). While addressing feelings of displacement and alienation, Starmer’s emphasis on national pride sometimes veered into exclusionary nationalism, inadvertently fuelling populist sentiments. This created fertile ground for Reform UK, which capitalised on public discontent with promises of strict immigration controls and enhanced national sovereignty. Reform UK’s success in the 2024 election, becoming the third-largest party with over four million votes, reflects this dynamic (Quinn, 2024). Analysing constituency results shows that Reform UK finished second in 98 constituencies, 89 of which were previously Labour held (ibid).

The recent race-related riots further illustrate extreme political participation through violence. Although these actions fall outside traditional democratic engagement, they reflect deep-seated grievances inadequately addressed by current political means (Tudor, 2024). Concentrated in seven of the ten most impoverished areas in the UK, including Blackburn, Blackpool, Hartlepool, Hull, Liverpool, Manchester, and Middlesbrough according to the government’s Indices of Deprivation, the riots highlight how long-standing economic deprivation and social marginalisation can lead to intense political expression (Harding, 2024 ). For Labour, the immediate challenge is not to respond with resentment, but to acknowledge concerns about identity and community while crafting a narrative that resonates with marginalised groups and delivers on economic fairness (Rutherford, 2024).

Understanding the geography of the riots is crucial for grasping the broader rise of populism. The shift from "pride in place" to "protection of place" reflects a significant change in how residents perceive their relationship with their environment and political system. In areas like Blackburn and Hull, where economic decline and social exclusion heighten feelings of disconnection, there is a stronger urge to protect local communities from perceived threats. This shift indicates deeper struggles over identity and place, fuelling both populist sentiment and violent responses.

To effectively counter these trends, Labour and other mainstream parties must engage with the specific socio-spatial dynamics driving populist and violent reactions. The riots are not merely responses to immediate grievances, but manifestations of deeper issues related to identity, belonging, and economic disparity. As Davidson (2024) notes, addressing these issues requires more than superficial policy changes; it demands a comprehensive approach that recognises and engages with the unique characteristics of these communities. By adopting this approach, Labour can work towards rebuilding trust and stability, fostering a genuinely inclusive and responsive political system.

Former Labour leader Neil Kinnock has advocated for a "positive and cumulative" approach driven by strong community purpose (Palmer, 2024 ). Labour’s strategy should therefore be multifaceted, addressing both economic and social challenges while fostering a sense of belonging and trust within communities. Expanding devolution, particularly through the concept of "double devolution," offers a critical opportunity for the Labour Party. Double devolution involves a two-tiered transfer of power: first, from central authorities to combined and local authorities, and second, from local governments to citizens and grassroots communities. This approach aims to transform governance from a distant bureaucracy into a more responsive and intimate system (Hilder, 2006) (McCann, 2019 ).

Nevertheless, implementing double devolution is not without its complexities (Johnston, 2012). Addressing economic and social disparities that often leave communities stretched thin and struggling to engage meaningfully in democratic processes is a significant challenge (Hickson, 2024 ). The daily demands of survival can overshadow active participation, while a lack of trust between central and local governments and inadequate infrastructure for local engagement further complicate efforts. There is also the risk of tokenism, where decentralisation efforts may create an illusion of autonomy without providing genuine empowerment to local communities. To overcome these challenges, it is crucial to develop a comprehensive framework that addresses local and regional needs and perspectives. This framework should enhance public consultation and engagement, promote bottom-up policymaking, and ensure that citizen participation is both meaningful and impactful. By focusing on these elements, double devolution has the potential to create a more responsive, accountable, and participatory governance system, fundamentally reshaping the relationship between citizens and their government.

Labour’s recent victories in local and mayoral elections, including control of nine out of ten metro mayoral positions and being the largest party in local government, demonstrate its potential to engage with diverse socio-spatial identities (Baker, 2024). This success reflects the party’s ability to mobilise support across different levels of government and implement policies that resonate with local populations. Leveraging its legacy of localism and solidarity, Labour has the opportunity to lead a transformative project of English devolution, potentially mirroring the profound impact of the Attlee Government’s post-1945 welfare state reforms. Geography plays a pivotal role in shaping the structure and operation of representative democracy (Ormerod, 2021), and Labour must adeptly navigate socio-spatial dynamics (Wills, 2017). By addressing deep geographical and economic divides through devolution, Labour could tackle political dormancy, growing cynicism, and the rise of populism. If executed effectively, Labour’s devolution strategy could foster a more resilient and participatory democratic framework, ultimately restoring public trust and engagement.

As we confront these challenges, the imperative is clear: to transform the landscape of democracy not merely through interpretation but through meaningful, participatory change.

References

Baker, K. Z. (2024, July 5 ). How big is the Labour government’s majority? Retrieved from Institute for Government : https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/explainer/government-majority

Barber, B. R. (1984). Strong Democracy: Participatory Democracy for a New Age. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Diamond, J. S. (2023, December 11). The Labour Party and the politics of devolution. Retrieved from Bennett Institute for Public Policy: Cambridge : https://www.bennettinstitute.cam.ac.uk/blog/labour-party-devolution/

Halvorsen, S. (2020). The geography of political parties: Territory and organisational strategies in Buenos Aires. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 45 , 242-255.

Harding, T. (2024 , August 10 ). Decades of deprivation behind UK riots present an immediate challenge for Keir Starmer. Retrieved from The National : https://www.thenationalnews.com/news/uk/2024/08/10/decades-of-deprivatio...

Hernández, E. (2018). Democratic discontent and support for mainstream and challenger parties: Democratic protest voting. European Union Politics, 19(3), 458-480. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116518770812

Hickson, D. J. (2024 ). Double devolution: towards a local perspective . Liverpool: Heseltine Institute .

Hilder, P. (2006). Power up, people: Double devolution and beyond . Public Policy Research 13(4), 238-248.

Inglehart, P. N. (2019). Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism . Cambridge : Cambridge University Press. .

Jenkin, T. P. (1950). The British General Election of 1950. The Western Political Quarterly, Vol.3, No.2, 179=189.

Johnston, L. (2012). Double devolution at the crossroads? Lerssons in delivering sustainable area decentralisation. In J. D. Liddle, Emerging and potential trends in public management: an age of austerity (pp. 129-159). Bingley: Emerald.

Levelling Up, H. a. (2024). Electoral Registration: Fourth Report of Session 2023–24. London: UK Parliament. Retrieved from https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm5804/cmselect/cmcomloc/58/report...

Malik, N. (2024, July 15). Hidden behind the celebration of Labour's landslide win is depressing disfranchisement . Retrieved from The Guardian : https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/article/2024/jul/15/labour-lan...

Massey, D. (1994). A Global Sense of Place. In D. Massey, Space, Place and Gender . Minneapolis : University of Minnesota Press.

McCann, P. (2019 ). UK Research and Innovation: A place-based shift . Cambridge : University of Cambridge .

OBE, D. N. (2014 ). Combatting the decline of mass politics. London : UK Parliament, Crown Copyright.

Ormerod, D. E. (2021). The place of politics and the politics of place: Housing, the Labour Party and the local state in England. Political Geography, volume 85 .

Palmer, M. (2024 , June 29 ). Kinnock urges Labour to combat Reform's nationalism. Retrieved from BBC NEWS : https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c51yjqgp792o

Powell, G. B. (1982). Contemporary Democracies: Participation, Stability and Violence . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Prime Minister's Office, 1. D. (2024 ). Speech: Keir Starmer's first speech as Prime Minister: 5 July 2024. London: Crown Copyright .

Quinn, E. A. (2024, July Friday 5th ). 'We're coming for Labour: Reform's small seat count conceals the size of its threat' . Retrieved from The Guardian : https://www.theguardian.com/politics/article/2024/jul/05/reform-few-seat...

Robinson, D. (2024 , July 10 ). The new front line of British politics is just lovely. Retrieved from The Economist : https://www.economist.com/britain/2024/07/10/the-new-front-line-of-briti...

Rutherford, J. (2024, August 10). Hatred and Division in Deep England. Retrieved from The New Statesman: https://www.newstatesman.com/comment/2024/08/hatred-and-division-in-deep...

Stoker, G. (2006). Why politics matters: making democracy work. Basingstoke: Palgrave, Macmillan.

Swyngedouw, J. W. (2015). The post-political and its discontents. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

The Consevative Party. (1950). This is the Road: The Conservative and Unionist Party's Policy. Retrieved from Consevative Party Manifestos: http://www.conservativemanifesto.com/1950/1950-conservative-manifesto.shtml

Tudor, S. (2024). Kings Speech 2024: Devolved Affairs. London: House of Lords. Retrieved from https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/LLN-2024-0031/LL...

Valgarðsson, D. P. (2024). Half of us: Turnout patterns at the 2024 general election. London: IPPR. Retrieved from https://www.ippr.org/articles/half-of-us

Wheeler, B. (2015, April 6). Are British general elections stuck in the 1950s? Retrieved from BBC NEWS: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/election-2015-32116219

Whiteley, P. (2012). Political Participation in Britain: The Decline and Revival of Civic Culture. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Will Jennings, N. C. (2017). The Decline in Diffuse Support for National Politic: The Long View on Political Discontent in Britain. Public Opin Q; 81(3), 748-758. doi:10.1093/poq/nfx020

Wills, J. S. (2017). The geography of the political party: Lessons from the British Labour Party's experiment with community organising, 2010 to 2015. Political Geography, volume 60 , 121-131.