Boats, Boundaries & Belonging: A Reading of Conservative Anti-Migration Campaigns Through the Gendered Grammar of the Home

Caitlin Rajan is a third-year undergraduate student at Trinity Hall here in Cambridge. She is specialising in Sociology in her final year of the Human, Social, and Political Sciences Tripos, and is president of the Cambridge University Sociology Society.

In this blog she shows how gendered ideas of the home and domesticity are used as a grammar to make legible the social and cultural fears that political campaigns propagate and harness.

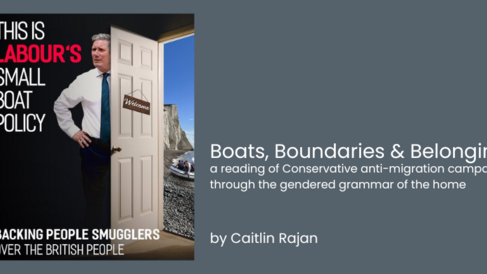

The image above, a poster disseminated via the @Conservatives X (previously Twitter) account, depicts Keir Starmer, leader of the UK Labour Party, standing by an open door upon which hangs a welcome sign. Beyond the doorway is an image of a migrant boat docking on a nondescript English shore - an image now used avidly by the Conservative Party in their ‘Stop the Boats’ campaign. Text on the poster reads, “This is Labour’s Small Boat Policy […] Backing People Smugglers over the British People”.

In one sense, the aim of the poster is clear: ignite fear that migrants are being freely welcomed, encouraged even, into the UK. Even more simply put, it says, ‘we do not want migrants here’. Who ‘we’ are is left intentionally ambiguous, inclusive of the viewer by positing the beholder as inside of the home. The ‘us’ is defined more by the existence of a clear ‘them’. So, in another sense, there is something far more illicit at work. Namely that these messages are being communicated through a number of symbols, ones that are not by any means new, but deeply historical. As I will come to argue, the effectiveness of this poster is in its mobilisations of a gendered grammar of the home that equates the nation with the home space. In doing this, the Conservatives knowingly encourage concern, fear, and a looming sense of threat, all of which the individual is encouraged to secure against by voting Conservative. Accordingly, I suggest that treating gendered ideas of the home and domesticity as a grammar through which we can read the Conservative nationalist anti-migrant campaign makes legible the real social and cultural fears that such campaigns propagate and harness.

Feminist politics has for a long time now highlighted the home as a gendered space (Briggs, 2017). Ideas of the happy housewife, played out in popular media in advertising, have created the figure of an individual responsible for childrearing, domestic and emotional labour, with the maintenance of the house as the site for this to occur (Davis, 1981; Federici, 2012). Subsequently suggested was the importance of not just a house, but a home – a space that is created (usually by the housewife) as a private sphere, a site of security, and, crucially, where biological but equally social and cultural reproduction of values occur (Erel, 2018). Nuclear families, poignantly the image of young children within the home, are significations of traditional values being reproduced into the next generation, providing comfort in continuity. Conceptually ‘home’ then became not just about the literal home space, but equally the production of a gendered grammar of the home – a grammar in a technological sense, akin to how Spillers (1987) conceives of it, as a structuring system for our ideas and understanding. As I will explore, this gendered grammar of the home has become a proxy through which our understanding and discourse around many other topics has formed.

Symbolic narratives around the home gained further power with the rise of neoconservatism under the Thatcher-Reagan era. As Graff & Walters (2019) contend, with new expectations loaded onto the individual to securitise the circumstances of themselves and their family, the home became an even more guarded space. So too in the neoliberal era does this instinct prevail. Ownership of the home is emblematic of what one has ‘earnt’ for themselves in as much an economic and material sense as a social and cultural one. One’s house is owned by them, and the desire to establish permanence and security is not just about the home, but a desire to hold onto the economic and social security the home is symbolically bound up with. Given its loaded meaning, no wonder the ‘home’ has now become a grammar through which nationalism is spoken of in the present.

As in the Conservative poster above, the home and the nation are drawn together as symbols so closely they are practically referenced interchangeably. It is an image, I argue, that must be read through the gendered grammar of the home to be truly legible in meaning and impact. The image implies the door to the nation and the door to the home is one and then same. Migrants then are not just crossing the bounded territory of the nation but entering the home space. Through the eyes of the gendered grammar of the home, migrants are then suggested to be a physical, economic, social, and cultural threat.

Further, in this image, they are portrayed as not just arriving, but quite literally on our doorstep. Such an image mobilises the affective. Our sites of reproduction are threatened. Our house is no longer guaranteed to be ours. Notions of ‘governmental belonging’ as Hage (2002) claims, describing the right one has to call the nation a home, feel threatened. It harnesses the individual instinct to guard oneself and the home, particularly given, as we have explored, the home has increasingly become a site to which one attributes social and cultural security. Migrants then represent the threat not just of physical entry into the nation, but the fear that the economic provision, social values, and cultural norms that are bolstered in our home are threatened also.

I would argue a crucial symbolic point to note is the intentional juxtaposing imagery of the temporary location of the boat and the permanent status of the home. The Conservative Party has made “Stop The Boats” their official slogan for anti-migrant policy. Why the emphasis on the boat? I argue that here home grammar is being deployed again to divide the ‘us’ from the ‘them’ via such contrasting images. Boats are symbolically read in a few central ways: they are insecure spaces, antiquated call-backs to colonialism suggesting both the ‘old-fashioned’ and an incompatibility with ‘modern Britain’, as well as conjuring to the imagination images of ‘invaders’ on shorelines. Most crucially, boats are a temporary space; in this way their

temporality conveys a lot of what Conservatives are suggesting migrants are – undocumented, unentitled to residency (again the language of which is closely tied to the home) and thus unwelcome. In contradistinction to the boat is the home. As we’ve explored the home is site of security, made by homemakers, private and, crucially, permanent. The temporary boat space vs the settled home space is an insidious use of grammar. It does not just convey ideas of invasion and fear of threats toward the home space, it fundamentally emphasises divisions: boat vs home, temporary vs permanent, documented vs undocumented, legal vs illegal, welcome vs unwelcome, and, hidden under the guise of the grammar, British vs non-British.

Lines between the boundaries of the nation-state and that of the home may be blurred in this image but the intentionality of doing so remains crystal clear. The Conservative Party, I argue, mobilise notably gendered notions of home and domesticity as grammars through which to talk about safeguarding the nation and to stoke nationalist sentiments. By relating the home to the nation, the national threat of migrants is made all the more affective. Opening the ‘national door’ to immigrants is seen as opening up the home to the cultural and social values of the ‘other’ which we are warned to be fearful of. Individuals are made to feel they must act to secure their home space and keeping migrants out of the nation is posited as the only solution. What is becoming increasingly clear is nationalist, anti-migrants campaigns are mobilising grammars and so the overt is allowed to be said implicitly, harnessing the power of affect and images. I emphasise the contradistinction between boats and the home as powerful imagery to this end. In this sense, conflating the nation and the home through a gendered grammar has become one of the most powerful tools in modern migrant discourse.

Bibliography

Briggs, L. (2017). How All Politics Became Reproductive Politics. University of California Press.

Davis, A. Y. (1981). Women, Race & Class. Vintage.

Erel, U. (2018, May). Saving and reproducing the nation: Struggles around right-wing politics of social reproduction, gender and race in austerity Europe. In Women's Studies International Forum (Vol. 68, pp. 173-182). Pergamon.

Federici, S. (2012). Revolution at point zero: Housework, reproduction, and feminist struggle.

Graff, A., Kapur, R., & Walters, S. D. (2019). Introduction: Gender and the rise of the global right. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 44(3), 541-560.

Hage, G. (Ed.). (2002). Arab-Australians today: Citizenship and belonging. Melbourne University Publish.

Spillers, H. (1987). Mama's baby, Papa's maybe. Diacritics