This blog by Dr Valentina Ausserladscheider, a recent PhD student at the Department of Sociology, was long-listed for The Loop's Best Blog Prize 2023.

Germany recently announced an increase in defence spending, reflecting a broader European shift in response to the war in Ukraine. Using the concept of path dependency, Dr Ausserladscheider suggests that this shift breaks with the founding idea of peace in the European Union

In response to ‘Putin's war’, Germany has decided to increase military expenditure by €100 billion. Adverts to join the military have become increasingly prevalent on social media channels and other platforms across Europe. The apparent logic in these actions is an assumption that Europe needs a strong geopolitical stance – represented through a military force – comparable to other geopolitical powers.

While I understand the logic of such accounts, I am concerned about its impact on Europe's role in diplomatic relations and the EU's founding vision of peace. History has taught us that such decisions and changes in public debate might have lasting consequences, long after the events which initially motivated those actions have passed. The potential consequences could be highly problematic.

Defence spending and its path dependency

Path dependency refers to the dynamic by which specific actions or events sometimes unintentionally and unpredictably shape the future development of the broader context in which this action takes place. This can lead to so-called 'lock-ins' when an action receives positive feedback in the short run and thus shapes actions going forward, limiting the scope for change. These actions thereby 'lock in' institutional patterns, despite the uncertainty over their prospective positive impacts.

Increasing military expenditure and investment in security policy in response to conflicts and crises elsewhere has often produced lasting effects. For instance, actions taken in response to 9/11 have had notable path dependencies. The context and events were very different to what we're witnessing today, but it is nevertheless worthwhile to highlight them.

After 9/11, the US and the UK announced a ‘war on terror’. This led to unprecedented defence spending domestically and internationally. Airport security controls have become normalised across the world – a lock-in effect of the war on terror, if you will. Moreover, its direct consequences still prevail today. These include militarisation of borders, humanitarian crises in countries such as Afghanistan and Iraq, and exclusionary immigration policies.

The public narratives on terrorism have continued to shape political discourse since 9/11 and the 'war on terror'

The public narratives on terrorism have continued to shape political discourse ever since. The ‘orientalist vision’ is a key feature in anti-terror discourse, which effectively legitimises the use of force on radical groups. In addition, political leaders portray terrorism as an external threat, and mobilise against it to achieve their goals. Thus, we see the ‘securitising’ of external threats to justify changes in immigration policies and asylum rights, making them more exclusionary. As such, the war on terror has had lasting effects on the legitimation of often xenophobic policies.

Breaking with the EU's founding idea of peace?

The increase in EU member states' defence spending is currently well received, given the catastrophic events in Ukraine. However, these examples of path dependent developments should raise concern about the potential consequences of higher military expenditure. In particular, I believe this threatens one of the founding principles of the EU.

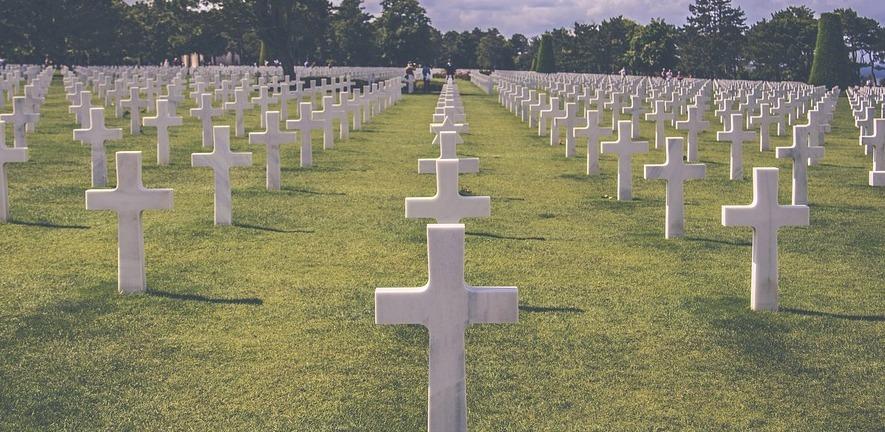

The European project was born as a reaction to the atrocities of the World Wars. It sought to establish an institution that would help prevent history from repeating itself. European integration through economic means was meant to foster peaceful unity and economic welfare. A single market, a single currency, and other common regulatory structures would not only create economic interdependence, making war extremely costly. They would also incentivise market transactions, ultimately leading to greater economic welfare across European countries.

The European project was born in reaction to the World Wars, to prevent history from repeating itself

For a long time, Europe focused on economic integration rather than defining common security and defence policies. However, Russia's annexation of Crimea and other challenges led to a push for new EU-level defence efforts in 2016. We should regard such efforts with concern. However, what we are experiencing today is domestic fiscal spending to strengthen nation-state-level defence capabilities.

The rise in military expenditure in Germany, which traditionally favours austerity over fiscal spending, is a particular surprise. The EU has faced many challenges through recent decades, which have exposed its architectural weaknesses. After the 2008 financial crisis, scholars and other commentators called for a fiscal union to match Europe's monetary integration. With the exception of the Covid-19 recovery fund, Germany has strongly opposed European fiscal unity. In this light, its push for domestic military expenditure seems to run counter to European efforts to foster peace through deeper economic integration.

Europe as a role model for peace through diplomacy

The concept of path dependency is particularly helpful to highlight the potential long-term dangers of an increase in defence spending. In the past, similar actions have led to unforeseeable and undesirable consequences.

Taking the EU's founding idea of peace and prosperity seriously means negating defence spending – and its potential consequences

Taking seriously the EU's founding idea of peace and prosperity through economic integration means negating defence spending, especially at national levels. While others suggest military intervention is the best way forward, my view is that the EU and its member states should become role models for diplomacy, just as they aim to be role models for the Green Transition.

This article was originally published at The Loop and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.