by Margarita Martens and Tekla Iashagashvili

In November, members of the Media and Culture MPhil pathway travelled to London to visit the Tate Modern and pop-up exhibition The Glass Room. During this field trip, we tried to connect the ideas of media and culture theorists we have covered in our seminars so far – such as the Frankfurt School, Jürgen Habermas, Pierre Bourdieu, Howard Becker, the medium theorists, and Sarah Thornton – with modern incarnations of the art world.

As Thornton writes in Seven Days in the Art World, ‘If the art world shared one principle, it would probably be that nothing is more important than the art itself.’ According to this, the self-declared mission of the Tate is ‘to promote public understanding and enjoyment of British, modern and contemporary art.’

The Tate consists of four art galleries: Tate Britain, Tate Modern, Tate Liverpool and Tate St Ives. The Tate Modern is housed in an imposing, red brick building which used to be a power station. Some of us were amused at the architectural similarities with our own University Library. But similarities quickly fade as one steps inside the gallery; colorful carpeting and the excited chatter of visitors swinging in twos and threes in the Turbine Hall’s SUPERFLEX exhibition erases the memory of the cathedral-like atmosphere of the UL.

Our tour started around these very swings and progressed upwards to thematically arranged exhibits. One of the most memorable of these was Artist and Society. We spent some time in a room devoted to Joseph Beuys, one of the most influential cultural protagonists of the twentieth century. As a German social activist, Beuys regarded art as an essential component of societies and declared that ‘everyone is an artist.’ Through the participatory character of his works, he – like Becker – raises the question of who actually gives art its significance – the artist or the spectator? Overall, the gallery celebrates Beuys’ life as his ‘artwork.’ In addition to German posters mentioning reforms that he championed during his life, blackboards with Beuys’ notes on them are on display in the gallery. These blackboards were used by Beuys when he lectured at the Tate in 1972. The museum’s exhibition of these blackboards as ‘art’ indicates the additional role of institutions in defining boundaries of the concept of art.

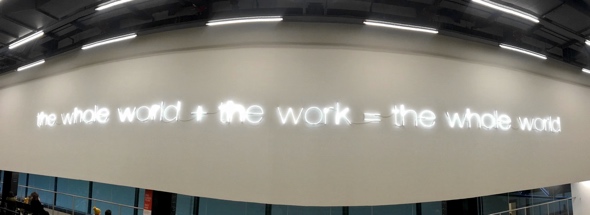

‘the whole world + the work = the whole world’ – this statement by Martin Creed, which appears in a hallway connecting two exhibits, became a topic of discussion. Does ‘the work’ equal zero? What is ‘the whole world’? Who is making this statement? Why was the idea conveyed in written form? Drawing on Bourdieu, what kind of cultural competence does one need to understand this statement, if any? Can the statement be read as privileged or patronizing? Does it convey the disinterestedness that, according to Bourdieu, is one of the hallmarks of art worlds? Is this statement an example of ‘the economic world reversed’?

Still contemplating answers to these questions, we moved to the Media Networks exhibition. In one of the dimly lit rooms, quotations of artists, social thinkers and Twitter users about art, creativity, communication and modernity are projected on plaques on the wall in Barbara Kruger’s Who Owns What? To our delight, quotes from familiar thinkers like Marshall McLuhan and Walter Benjamin appeared on the screens, as did a tweet from one of our group members who had used the exhibition’s hashtag, #TateNetworks.

We concluded our tour of the Tate in a room in which a tower of radios – Babel by Cildo Meireles – emitted incomprehensible chatter. Here as well, Bourdieu, McLuhan and Habermas were brought up as we contemplated the future of communication, truth and facts, and society.

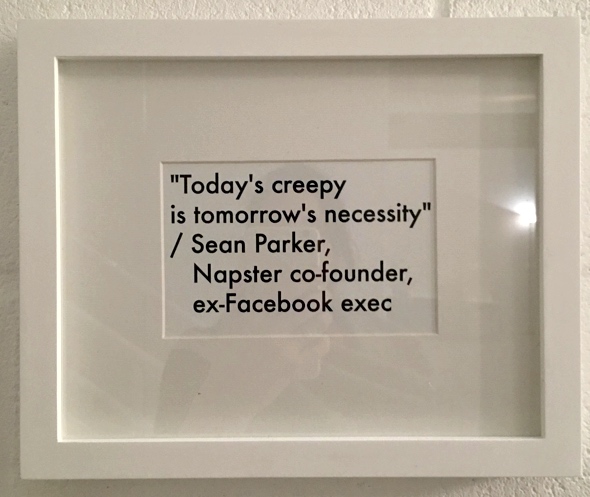

Our field trip in London finished in The Glass Room exhibition, a collaboration between Tactical Tech and Mozilla where we discovered the newest digital consumer products such as high-tech digital pills, facial recognition software, volumes containing hacked passwords, personality tests based on one’s usage of social media and jarring quotes from Google executives that made us question whether the fight for privacy is a lost cause. Overall, the Glass Room embodies the transparency of today’s society within the virtual sphere – literally, a Glass Room.

In true academic fashion, this fieldwork produced many more questions than answers. We would like to thank Dr Ella McPherson for proposing this trip, the Department of Sociology for providing funds to subsidize our costs, and Tom Wadsworth, our fellow MPhil student, who found time to take care of all the logistical matters.